Cincinnati

Cincinnati | |

|---|---|

| Nicknames: | |

| Motto(s): Juncta Juvant (Latin) "Strength in Unity" | |

Interactive map of Cincinnati | |

| Coordinates: 39°06′00″N 84°30′45″W / 39.10000°N 84.51250°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Hamilton |

| Settled | 1788 |

| Incorporated (town) | January 1, 1802[2] |

| Incorporated (city) | March 1, 1820[3] |

| Named for | Society of the Cincinnati and Cincinnatus |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Cincinnati City Council |

| • Mayor | Aftab Pureval (D) |

| • City manager | Sheryl Long |

| Area | |

| • City | 79.64 sq mi (206.26 km2) |

| • Land | 77.91 sq mi (201.80 km2) |

| • Water | 1.72 sq mi (4.46 km2) |

| • Metro | 4,808 sq mi (12,450 km2) |

| Elevation | 742 ft (226 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

| • City | 309,317 |

| • Estimate (2023)[6] | 311,097 |

| • Rank | US: 64th |

| • Density | 3,969.98/sq mi (1,532.81/km2) |

| • Urban | 1,686,744 (US: 33rd) |

| • Urban density | 2,242.2/sq mi (865.7/km2) |

| • Metro | 2,265,051 (US: 30th) |

| • Demonym | Cincinnatian |

| GDP | |

| • Cincinnati (MSA) | $157.0 billion (2022) |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (EST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (EDT) |

| ZIP Codes | 452XX, 45999[8] |

| Area code | 513 and 283 |

| FIPS code | 39-15000[9] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1086201[5] |

| Website | cincinnati-oh |

Cincinnati (/ˌsɪnsɪˈnæti/ SIN-si-NAT-ee; nicknamed Cincy) is a city in and the county seat of Hamilton County, Ohio, United States.[10] Settled by Europeans in 1788, the city is located on the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line with Kentucky. The population of Cincinnati was 309,317 in 2020, making it the third-most populous city in Ohio after Columbus and Cleveland and 64th in the United States. The city is the economic and cultural hub of the Cincinnati metropolitan area, Ohio's most populous metro area and the nation's 30th-largest with over 2.265 million residents.[11]

Throughout much of the 19th century, Cincinnati was among the top 10 U.S. cities by population. The city developed as a river town for cargo shipping by steamboats, located at the crossroads of the Northern and Southern United States, with fewer immigrants and less influence from Europe than East Coast cities in the same period. However, it received a significant number of German-speaking immigrants, who founded many of the city's cultural institutions. It later developed an industrialized economy in manufacturing. Many structures in the urban core have remained intact for 200 years; in the late 1800s, Cincinnati was commonly referred to as the "Paris of America" due mainly to ambitious architectural projects such as the Music Hall, Cincinnatian Hotel, and Roebling Bridge.[12]

Cincinnati has the twenty-eighth largest economy in the United States and the fifth largest in the Midwest, home to several Fortune 500 companies including Kroger, Procter & Gamble, and Fifth Third Bank.[13] It is home to three professional sports teams: the Cincinnati Reds of Major League Baseball; the Cincinnati Bengals of the National Football League; and FC Cincinnati of Major League Soccer; it is also home to the Cincinnati Cyclones, a minor league ice hockey team. The city's largest institution of higher education, the University of Cincinnati, was founded in 1819 as a municipal college and is now ranked as one of the 50 largest in the United States.[14] The Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals is based in the city.

Cincinnati is the birthplace of William Howard Taft, the 27th President and 10th Chief Justice of the United States. Recently, Cincinnati has been named among the 100 most livable cities in the world, at number 88, and is on many Best Places to Live lists, including Livability.com and U.S. News & World Report. Forbes ranked Cincinnati as the 5th best city for young professionals in 2023.[15]

History

[edit]Etymology

[edit]Two years after the founding of the settlement then known as "Losantiville", Arthur St. Clair, the governor of the Northwest Territory, changed its name to "Cincinnati", possibly at the suggestion of the surveyor Israel Ludlow,[16] in honor of the Society of the Cincinnati.[17] St. Clair was at the time president of the Society, made up of Continental Army officers of the Revolutionary War.[18] The club was named for Lucius Quinctius Cincinnatus, a dictator in the early Roman Republic who saved Rome from a crisis and then retired to farming because he did not want to remain in power, becoming a symbol of Roman civic virtue.[19][20][a]

Early history

[edit]

Cincinnati began in 1788 when Mathias Denman, Colonel Robert Patterson, and Israel Ludlow landed at a spot at the northern bank of the Ohio opposite the mouth of the Licking and decided to settle there. The original surveyor, John Filson, named it "Losantiville", a combination of syllables drawn from French and Latin words, intended to mean "town opposite the mouth of the Licking".[23][24] On January 4, 1790, St. Clair changed the name of the settlement to honor the Society of the Cincinnati.[25]

In 1811, the introduction of steamboats on the Ohio River opened up the city's trade to more rapid shipping, and the city established commercial ties with St. Louis, Missouri, and New Orleans downriver. Cincinnati was incorporated as a city on March 1, 1819.[26] Exporting pork products and hay, it became a center of pork processing in the region. From 1810 to 1830, the city's population nearly tripled, from 9,642 to 24,831.[27]

Construction on the Miami and Erie Canal began on July 21, 1825, when it was called the Miami Canal, related to its origin at the Great Miami River. The first section of the canal was opened for business in 1827.[28] In 1827, the canal connected Cincinnati to nearby Middletown; by 1840, it had reached Toledo.

Railroads were the next major form of commercial transportation to come to Cincinnati. In 1836, the Little Miami Railroad was chartered.[29][page needed] Construction began soon after, to connect Cincinnati with the Mad River and Lake Erie Railroad, and provide access to the ports of the Sandusky Bay on Lake Erie.[28][page needed]

During the time, employers struggled to hire enough people to fill positions. The city had a labor shortage until large waves of immigration by Irish and Germans in the late 1840s. The city grew rapidly over the next two decades, reaching 115,000 people by 1850.[18]

During this period of rapid expansion and prominence, residents of Cincinnati began referring to the city as the Queen City.[30]

Industrial development and Gilded Age

[edit]

Cincinnati's location, on the border between the free state of Ohio and the slave state of Kentucky, made it a prominent location for slaves to escape the slave-owning south. Many prominent abolitionists also called Cincinnati their home during this period, and made it a popular stop on the Underground Railroad.[31] In 2004, the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center was completed along Freedom Way in Downtown, honoring the city's involvement in the Underground Railroad.[32]

In 1859, Cincinnati laid out six streetcar lines; the cars were pulled by horses and the lines made it easier for people to get around the city.[29] By 1872, Cincinnatians could travel on the streetcars within the city and transfer to rail cars for travel to the hill communities. The Cincinnati Inclined Plane Company began transporting people to the top of Mount Auburn that year.[28] In 1889, the Cincinnati streetcar system began converting its horse-drawn cars to electric streetcars.[33]

The Second Annual Meeting of the Woman's Christian Temperance Union was held in Cincinnati in November 1875.[34]

In 1880, the city government completed the Cincinnati Southern Railway to Chattanooga, Tennessee. It was the only municipally-owned interstate railway in the United States until its sale to Norfolk Southern in March 2024.[35][36]

In 1884, outrage over a manslaughter verdict in what many observers thought was a clear case of murder triggered the Courthouse riots, one of the most destructive riots in American history. Over the course of three days, 56 people were killed and over 300 were injured.[37] The riots ended the regime of Republican boss Thomas C. Campbell.

20th century

[edit]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Cincinnati had a population of 325,902. The city completed many ambitious projects in the 20th century starting with the Ingalls Building which was completed in 1903. An early rejuvenation of downtown began into the 1920s and continued into the next decade with the construction of Cincinnati Union Terminal, the United States Courthouse and Post Office, the Cincinnati Subway, and the 49-story Carew Tower, which was the city's tallest building upon its completion. Cincinnati weathered the Great Depression better than most American cities of its size, largely due to a resurgence in river trade, which was less expensive than transporting goods by rail. The Ohio River flood of 1937 was one of the worst in the nation's history and destroyed many areas along the Ohio valley.[38] Afterward the city built protective flood walls. After World War II, Cincinnati unveiled a master plan for urban renewal that resulted in modernization of the inner city. During the 1950s, Cincinnati's population peaked at 509,998. Since the 1950s, $250 million was spent on improving neighborhoods, building clean and safe low- and moderate-income housing, providing jobs and stimulating economic growth.[39]

21st century to present

[edit]At the dawn of the 2000s, Cincinnati's population stood at 331,285. The construction of Paul Brown Stadium (currently known as Paycor Stadium) in the year 2000 resulted from a sales tax increase in Hamilton County, as did the commencement of construction for Great American Ball Park, which later opened its doors in 2003.

The city experienced the 2001 Cincinnati riots, causing an estimated $3.6 million in damage to businesses and $1.5-2 million in damage to the city itself. Subsequently, substantial transformations unfolded, particularly in the process of gentrification within the Over-the-Rhine neighborhood.

In 2018, MLS announced the inclusion of FC Cincinnati, becoming the city's third professional sports team. TQL Stadium, located on Cincinnati's west end, was subsequently constructed and opened its doors in 2021. Notably, the 2020 census revealed that Cincinnati had witnessed a population growth, marking the first such increase since the 1950 census.

On January 4, 2022, Aftab Pureval assumed office as the 70th mayor of Cincinnati.

Nicknames

[edit]Cincinnati has many nicknames, including Cincy, The Queen City,[40] The Queen of the West,[41] The Blue Chip City,[42][43][44] and The City of Seven Hills.[45] These are more typically associated with professional, academic, and public relations references to the city, including restaurant names such as Blue Chip Cookies, and are not commonly used by locals in casual conversation, with the exception of Cincy, which is often used to refer to the city in absentia.[citation needed]

"The City of Seven Hills" stems from the June 1853 edition of the West American Review, "Article III—Cincinnati: Its Relations to the West and South", which described and named seven specific hills. The hills form a crescent around the city: Mount Adams, Walnut Hills, Mount Auburn, Vine Street Hill, College Hill, Fairmont (now rendered Fairmount), and Mount Harrison (now known as Price Hill). The name refers to ancient Rome, reputed to be built on seven hills.[citation needed]

"Queen City" is taken from an 1819 newspaper article[46] and further immortalized by the 1854 poem "Catawba Wine". In it, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow wrote of the city:

And this Song of the Vine,

This greeting of mine,

The winds and the birds shall deliver,

To the Queen of the West,

In her garlands dressed,

On the banks of the Beautiful River.[47]

For many years, Cincinnati was also known as "Porkopolis"; this nickname came from the city's large pork interests.[48]

Newer nicknames such as "The 'Nati" are emerging and are attempted to be used in different cultural contexts. For example, the local Keep America Beautiful affiliate, Keep Cincinnati Beautiful, introduced the catchphrase "Don't Trash the 'Nati" in 1998 as part of a litter-prevention campaign.[49][50][51]

Geography

[edit]The city is undergoing significant changes due to new development and private investment. This includes buildings of the long-stalled Banks project that includes apartments, retail, restaurants, and offices, which will stretch from Great American Ball Park to Paycor Stadium. Phase 1A is already complete and 100 percent occupied as of early 2013. Smale Riverfront Park is being developed along with The Banks, and is Cincinnati's newest park. Nearly $3.5 billion have been invested in the urban core of Cincinnati (including Northern Kentucky). Much of this development has been undertaken by 3CDC. The Cincinnati Bell Connector began in September 2016.[52][53]

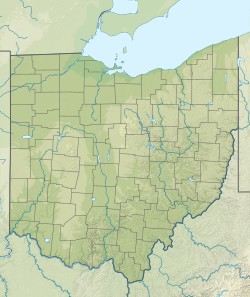

Cincinnati is midway by river between the cities of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and Cairo, Illinois. The downtown lies near the mouth of the Licking, a confluence where the first settlement occurred.[54] Metro Cincinnati spans southern Ohio, south-eastern Indiana, and northern Kentucky; the census bureau has measured the city proper at 79.54 square miles (206.01 km2), of which 77.94 square miles (201.86 km2) are land and 1.60 square miles (4.14 km2) are water.[55] The city spreads over a number of hills, bluffs, and low ridges overlooking the Ohio in the Bluegrass region of the country.[56] The tristate is geographically located within the Midwest at the far northern extremity of the Upland South.

Three municipalities are enveloped by the city: Norwood, Elmwood Place, and Saint Bernard. Norwood is a business and industrial city, while Elmwood Place and Saint Bernard are small, primarily residential, villages. Cincinnati does not have an exclave, but the city government does own several properties outside the corporation limits: French Park in Amberley Village and the disused runway at the former Blue Ash Airport in Blue Ash.

Cityscape

[edit]

Cincinnati has many landmarks across its area. Some of these landmarks are recognized nationwide, others are more recognized among locals. These landmarks include: Union Terminal, Carew Tower, Great American Tower, Fountain Square, Washington Park, and Great American Ballpark.

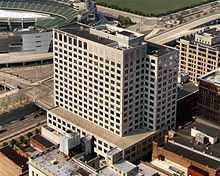

Cincinnati is home to numerous structures that are noteworthy due to their architectural characteristics or historic associations, including the aforementioned Carew Tower, the Scripps Center, the Ingalls Building, Cincinnati Union Terminal, and the Isaac M. Wise Temple.[57] Queen City Square opened in January 2011. The building is the tallest in Cincinnati and the third tallest in Ohio, reaching a height of 665 feet (203 m).[58]

Since April 1, 1922, the Ohio flood stage at Cincinnati has officially been set at 52 feet (16 m), as measured from the John A. Roebling Suspension Bridge. At this depth, the pumping station at the mouth of Mill Creek is activated.[59][60] From 1873 to 1898, the flood stage was 45 feet (14 m). From 1899 to March 31, 1922, it was 50 feet (15 m).[60] The Ohio reached its lowest level, less than 2 feet (0.61 m), in 1881; conversely, its all-time high water mark is 79 feet 11+7⁄8 inches (24.381 m), having crested January 26, 1937.[59][61] Various parts of Cincinnati flood at different points: Riverbend Music Center in the California neighborhood floods at 42 feet (13 m), while Sayler Park floods at 71 feet (22 m) and the Freeman Avenue flood gate closes at 75 feet (23 m).[59] Frequent flooding has hampered the growth of Cincinnati's municipal airport at Lunken Field and the Coney Island amusement park.[62] Downtown Cincinnati is protected from flooding by the Serpentine Wall at Yeatman's Cove and another flood wall built into Fort Washington Way.[63] Parts of Cincinnati also experience flooding from the Little Miami River and Mill Creek.

Neighborhoods

[edit]

Cincinnati consists of fifty-two neighborhoods. Many of these neighborhoods were once villages that have been annexed by the city, with many retaining their former names, such as Walnut Hills and Mount Auburn.[64] Westwood is the city's most populous neighborhood, with other significant neighborhoods including CUF (home to the University of Cincinnati) and Price Hill.[65]

Downtown Cincinnati is the city's central business district and contains a number of neighborhoods in the flat land between the Ohio River and uptown. These neighborhoods include Over-the-Rhine, Pendleton, Queensgate, and West End. Over-the-Rhine is among the largest, most intact urban historic districts in the United States.[66] Most of Over-the-Rhine's ornate brick buildings were built by German immigrants from 1865 to the 1880s.[67] The neighborhood has been intensely redeveloped in the 21st century, with a focus on fostering small businesses.[68]

Climate

[edit]| Cincinnati, Ohio | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Cincinnati is at the southern limit (considering the 0 °C or 32 °F isotherm) of the humid continental climate zone (Köppen: Dfa), bordering the humid subtropical climate zone (Cfa).

Summers are hot and humid, with significant rainfall in each month and highs reaching 90 °F (32 °C) or above on 21 days per year, often with high dew points and humidity. July is the warmest month, with a daily average temperature of 75.9 °F (24.4 °C).[69]

Winters tend to be cold and moderately snowy, with January, the coldest month, averaging at 30.8 °F (−0.7 °C).[69] Lows reach 0 °F (−18 °C) on an average 2.6 nights yearly.[69] An average winter will see around 22.1 inches (56 cm) of snowfall, contributing to the yearly 42.5 inches (1,080 mm) of precipitation, with rainfall peaking in spring.[70] Extremes range from −25 °F (−32 °C) on January 18, 1977, up to 108 °F (42 °C) on July 21 and 22, 1934.[71]

While snow in Cincinnati is not as intense as many of the cities located closer to the Great Lakes, there have been notable cases of severe snowfall, including the Great Blizzard of 1978, and more notable snowstorms in 1994, 1999, 2007, and 2021.

Severe thunderstorms are common in the warmer months, and tornadoes, while infrequent, are not unknown, with such events striking the Metro Cincinnati area most recently in 1974, 1999, 2012, and 2017.[72]

| Climate data for Cincinnati (Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Int'l), 1991–2020 normals,[b] extremes 1871–present[c] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 77 (25) |

79 (26) |

88 (31) |

90 (32) |

95 (35) |

102 (39) |

108 (42) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

95 (35) |

82 (28) |

75 (24) |

108 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 61.8 (16.6) |

66.1 (18.9) |

74.3 (23.5) |

81.1 (27.3) |

86.7 (30.4) |

91.6 (33.1) |

93.6 (34.2) |

93.2 (34.0) |

90.7 (32.6) |

82.9 (28.3) |

72.0 (22.2) |

63.8 (17.7) |

95.3 (35.2) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 39.6 (4.2) |

43.7 (6.5) |

53.5 (11.9) |

65.5 (18.6) |

74.5 (23.6) |

82.6 (28.1) |

86.0 (30.0) |

85.2 (29.6) |

78.9 (26.1) |

66.7 (19.3) |

53.8 (12.1) |

43.3 (6.3) |

64.4 (18.0) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 31.4 (−0.3) |

34.7 (1.5) |

43.6 (6.4) |

54.6 (12.6) |

64.1 (17.8) |

72.3 (22.4) |

75.9 (24.4) |

74.9 (23.8) |

68.1 (20.1) |

56.2 (13.4) |

44.4 (6.9) |

35.6 (2.0) |

54.7 (12.6) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 23.1 (−4.9) |

25.8 (−3.4) |

33.8 (1.0) |

43.7 (6.5) |

53.7 (12.1) |

62.1 (16.7) |

65.9 (18.8) |

64.6 (18.1) |

57.3 (14.1) |

45.7 (7.6) |

35.1 (1.7) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

44.9 (7.2) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 0.1 (−17.7) |

6.5 (−14.2) |

14.8 (−9.6) |

26.7 (−2.9) |

36.6 (2.6) |

49.2 (9.6) |

55.9 (13.3) |

54.6 (12.6) |

42.5 (5.8) |

29.8 (−1.2) |

19.0 (−7.2) |

9.1 (−12.7) |

−2.7 (−19.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −25 (−32) |

−17 (−27) |

−11 (−24) |

15 (−9) |

27 (−3) |

39 (4) |

47 (8) |

43 (6) |

31 (−1) |

16 (−9) |

0 (−18) |

−20 (−29) |

−25 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.30 (84) |

3.17 (81) |

4.16 (106) |

4.53 (115) |

4.67 (119) |

4.75 (121) |

3.83 (97) |

3.43 (87) |

3.11 (79) |

3.35 (85) |

3.23 (82) |

3.73 (95) |

45.26 (1,150) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 7.7 (20) |

6.7 (17) |

3.4 (8.6) |

0.4 (1.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.8 (2.0) |

4.1 (10) |

23.3 (59) |

| Average extreme snow depth inches (cm) | 3.5 (8.9) |

3.4 (8.6) |

2.0 (5.1) |

0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.4 (1.0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

6.0 (15) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 13.2 | 12.0 | 12.5 | 13.1 | 13.5 | 11.8 | 11.0 | 8.9 | 8.3 | 8.7 | 10.3 | 12.4 | 135.7 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 6.7 | 5.9 | 2.7 | 0.6 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 1.1 | 4.6 | 21.7 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 72.2 | 70.1 | 67.0 | 62.8 | 66.9 | 69.2 | 71.5 | 72.3 | 72.7 | 69.2 | 71.0 | 73.8 | 69.9 |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 19.9 (−6.7) |

22.5 (−5.3) |

31.3 (−0.4) |

39.6 (4.2) |

50.5 (10.3) |

59.7 (15.4) |

64.2 (17.9) |

63.0 (17.2) |

56.7 (13.7) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.7 (1.5) |

25.5 (−3.6) |

42.6 (5.9) |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 120.8 | 128.4 | 170.1 | 211.0 | 249.9 | 275.5 | 277.0 | 261.5 | 234.4 | 188.8 | 118.7 | 99.3 | 2,335.4 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 40 | 43 | 46 | 53 | 56 | 62 | 61 | 62 | 63 | 55 | 39 | 34 | 52 |

| Average ultraviolet index | 2 | 3 | 5 | 6 | 8 | 9 | 9 | 8 | 7 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 5 |

| Source 1: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[70][69][71][73] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: Weather Atlas (UV)[74] | |||||||||||||

Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

See or edit raw graph data.

Demographics

[edit]Graphs are unavailable due to technical issues. There is more info on Phabricator and on MediaWiki.org. |

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1800 | 850 | — |

| 1810 | 2,540 | +198.8% |

| 1820 | 9,642 | +279.6% |

| 1830 | 24,831 | +157.5% |

| 1840 | 46,338 | +86.6% |

| 1850 | 115,435 | +149.1% |

| 1860 | 161,044 | +39.5% |

| 1870 | 216,239 | +34.3% |

| 1880 | 255,139 | +18.0% |

| 1890 | 296,908 | +16.4% |

| 1900 | 325,902 | +9.8% |

| 1910 | 363,591 | +11.6% |

| 1920 | 401,247 | +10.4% |

| 1930 | 451,160 | +12.4% |

| 1940 | 455,610 | +1.0% |

| 1950 | 503,998 | +10.6% |

| 1960 | 502,550 | −0.3% |

| 1970 | 452,525 | −10.0% |

| 1980 | 385,460 | −14.8% |

| 1990 | 364,040 | −5.6% |

| 2000 | 331,285 | −9.0% |

| 2010 | 296,943 | −10.4% |

| 2020 | 309,317 | +4.2% |

| 2023 | 311,097 | +0.6% |

| Source: U.S. decennial census[75] 1810–1970[27] 1980–2000[76][77] 2010–2020[6] 2023 (est)[6] | ||

| Demographic profile | 2020[78] | 2010[79] | 2000[80] | 1990[81] | 1970[81] | 1950[81] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | 50.3% | 48.2% | 53.0% | 60.5% | 71.9% | 84.4% |

| —Non-Hispanic | 48.2% | 48.1% | 51.7% | 60.2% | 71.4%[82] | n/a |

| Black or African American | 41.4% | 44.8% | 42.9% | 37.9% | 27.6% | 15.5% |

| Hispanic or Latino (of any race) | 4.2% | 2.8% | 1.3% | 0.7% | 0.6% | n/a |

| Asian | 2.2% | 1.8% | 1.5% | 1.1% | 0.2% | 0.1% |

In 1950, Cincinnati reached its peak population of 503,998; thereafter, it lost population in every census count from 1960 to 2010. In the late 20th century, industrial restructuring caused a loss of jobs. More recently, the population has begun recovering: the 2020 census reports a population of 309,317, representing a 4.2% increase from 296,943 in 2010.[83] This marked the first increase in population recorded since the 1950 Census, reversing a 60-year trend of population decline.

At the 2020 census,[84] there were 309,317 people, 138,696 households, and 62,319 families residing in the city. The population density was 3,809.9 inhabitants per square mile (1,471.0/km2). There were 161,095 housing units at an average density of 2,066.9 per square mile (798.0/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 50.3% White, 41.4% African American, 0.1% Native American, 2.2% Asian, 0.1% Pacific Islander, 1.2% from other races, and 4.6% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 4.2% of the population.

There were 138,696 households, of which 25.4% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 23.2% were married couples living together, 19.1% had a female householder with no husband present, 4.4% had a male householder with no wife present, and 53.3% were non-families. 43.4% of all households were made up of individuals, and 9.9% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.09 and the average family size was 3.00.

The median age in the city was 32.5 years. 21.6% of residents were under the age of 18; 14.6% were between the ages of 18 and 24; 28.4% were from 25 to 44; 24.1% were from 45 to 64; and 10.8% were 65 years of age or older. The gender makeup of the city was 48.4% male and 51.6% female.[85]

As of the 2022 census estimates, the Cincinnati metropolitan area had a population of 2,265,051, making it the 30th-largest metropolitan statistical area in the country. It includes the Ohio counties of Hamilton, Butler, Warren, Clermont, Clinton, and Brown, as well as the Kentucky counties of Boone, Bracken, Campbell, Gallatin, Grant, Kenton, and Pendleton, and the Indiana counties of Dearborn, Franklin, Union, and Ohio.

Economy

[edit]Metropolitan Cincinnati has the twenty-eighth largest economy in the United States and the fifth largest in the Midwest, after Chicago, Minneapolis–St. Paul, Detroit, and St. Louis. In 2016, it had the fastest-growing Midwestern economic capital.[13] The gross domestic product for the region was $127 billion (~$160 billion in 2023) in 2015.[86] The median home price is $158,200, and the cost of living in Cincinnati is 8% below the national average. As of September 2022, the unemployment rate is 3.3%, below the national average.[87][88]

Several Fortune 500 companies are headquartered in Cincinnati, such as Kroger, Procter & Gamble, Western & Southern Financial Group, Fifth Third Bank, American Financial Group, and Cintas. General Electric has headquartered their Global Operations Center in Cincinnati; GE Aerospace is based in Evendale.[89] The Kroger Company employs over 20,000 people locally, making it the largest employer in the city; the other four largest employers are Cincinnati Children's Hospital, TriHealth, the University of Cincinnati, and St. Elizabeth Healthcare.[90] Cincinnati is home to a branch office of the Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland.[91]

Arts and culture

[edit]Society

[edit]

Cincinnati was platted and proliferated by American settlers, including Scotch Irish, frontiersmen, and keelboaters. For over a century and a half, Cincinnati went unchallenged as the most prominent of Ohio's cities, a role that earned it the nickname of "chief city of Ohio" in the 1879 New American Cyclopædia. In addition to this book, countless other books have documented the social history of both the city and its frontier people.[92][93][94][95] The city fathers, of Anglo-American families of prominence, were Episcopalian. Inspired by its earlier horseback circuit preachers, early Methodism was also important. The first established Methodist class in the Northwest Territory came 1797 to nearby Milford. By 1879, there were 162 documented church edifices in the city. For this reason, from the beginning, Protestantism has played a formative role in the Cincinnati ethos. Christ Church Cathedral continues the legacy of the early Anglican leaders of Cincinnati, noted by historical associations as being a keystone of civic history; and among Methodist institutions were The Christ Hospital as well as projects of the German Methodist Church.[96] One of Cincinnati's biggest proponents of Methodism was the Irish immigrant James Gamble, who together with William Procter founded Procter & Gamble; in addition to being a devout Methodist, Gamble and his estate donated money to construct Methodist churches throughout Greater Cincinnati.[97]

Cincinnati, being a rivertown crossroads, depended on trade with the slave states south of the Ohio River at a time when thousands of black people were settling in the free state of Ohio. Most of them came after the American Civil War and were from Kentucky and Virginia with many of them fugitives who had sought freedom and work in the North. In the antebellum years, the majority of native-born whites in the city came from northern states, primarily Pennsylvania.[98] Though 57 percent of whites migrated from free states, 26 percent were from southern states and they retained their cultural support for slavery. This quickly led to tensions between pro-slavery residents and abolitionists who sought lifting restrictions on free black people, as codified in the "Black Code" of 1804.[99] In the pre-Civil War period, Cincinnati had been called "a Southern city on free soil".[100]: 44 Volatile social conditions saw riots in 1829, when many black people lost their homes and property. As the Irish entered the city in the late 1840s, they competed with black people at the lower levels of the economy. White-led riots against black people occurred in 1836, when an abolitionist press was twice destroyed; and in 1842.[99] More than 1,000 black people abandoned the city after the 1829 riots. Black people in Philadelphia and other major cities raised money to help the refugees recover from the destruction. By 1842 black people had become better established in the city; they defended themselves and their property in the riot, and worked politically as well.[101]

Germans were among the earliest newcomers, migrating from Pennsylvania, Virginia and Tennessee. David Ziegler succeeded Arthur St. Clair in command at Fort Washington. After the conclusion of the Northwest Indian War and removal of Native Americans to the west, he was elected as Cincinnati's first town president in 1802.[102][103] Cincinnati was influenced by Irishmen, and Prussians and Saxons (northern Germans), seeking to emigrate away from crowding and strife. In 1830, residents with German roots made up 5% of the population, as many had migrated from Pennsylvania; ten years later this had increased to 30%.[104] Thousands of Germans entered the city after the German revolutions of 1848–49, and by 1900, more than 60 percent of its population was of Prussian background.[105] The menial-jobbed, aggravated Irish often organized mobs, and the Germans, far away from their Pennsylvania Dutch connections, did the same. Traditions and celebrations of the city's immigrant communities have been sustained; nearby Waynesville hosts the yearly Ohio Sauerkraut Festival,[106] and Cincinnati hosts several big yearly events which commemorate connections to the Old World. Oktoberfest Zinzinnati,[107] Bockfest,[108] and the Taste of Cincinnati feature local restaurateurs.

Cincinnati's Jewish community was developed by those from England and Germany. A large segment of the community, led by Isaac M. Wise, developed Reform Judaism in response to the influences of the Enlightenment and making their new lives in the United States. Rabbi Wise, known as a founding father of the Reform movement, and his contemporaries, bore a great influence on the Jewish faith in Cincinnati, the United States, and worldwide.[109]

The NRHP-listed Potter Stewart United States Courthouse is a federal court, the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, one of thirteen United States courts of appeals. Federal Reserve Bank of Cleveland Cincinnati Branch is located across the street from the East Fourth Street Historic District.

Museums

[edit]The Cincinnati Art Museum is an art museum in the Eden Park neighborhood. Founded in 1881, it was the first purpose-built art museum west of the Allegheny Mountains. Its collection of over 67,000 works spanning 6,000 years of human history make it one of the most comprehensive collections in the Midwest.[110] The Contemporary Arts Center was established in 1939 as one of the first contemporary art institutions in the country. The Art Academy of Cincinnati also features three public galleries, in addition to the Taft Museum of Art collection.[111]

The city's Cincinnati Museum Center complex operates out of the Cincinnati Union Terminal in the Queensgate neighborhood. Within the complex are the Cincinnati History Museum, Museum of Natural History & Science, Robert D. Lindner Family Omnimax Theater, Cincinnati History Library and Archives, and Duke Energy Children's Museum.[112] The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center opened in 2004 along the riverfront based on the history of the Underground Railroad, recognizing the role the city played in its history as thousands of slaves escaped to freedom by crossing the Ohio River from the southern slave states.[111] U.S. president and chief justice William Howard Taft's childhood home, now the William Howard Taft National Historic Site, in Mount Auburn features exhibits on Taft's life and accomplishments.[113]

The American Sign Museum features over 200 signs and other objects on display ranging from the late nineteenth century to the 1970s.[114]

Music

[edit]

Music-related events include the Cincinnati May Festival, Bunbury Music Festival, and Cincinnati Bell/WEBN Riverfest. Cincinnati hosted the World Choir Games in 2012 with the mantra "Cincinnati, the City that Sings!"

Cincinnati has given rise or been home to popular musicians and singers, including Lonnie Mack, Doris Day, Odd Nosdam, Dinah Shore, Fats Waller, Rosemary Clooney, Bootsy Collins, The Isley Brothers, Merle Travis, Hank Ballard, Otis Williams, Mood, Midnight Star, Calloway, The Afghan Whigs, Over the Rhine, Blessid Union of Souls, Freddie Meyer, 98 Degrees, The Greenhornes, The Deele, Enduser, Heartless Bastards, The Dopamines, Adrian Belew, The National, Foxy Shazam, Why?, Wussy, H-Bomb Ferguson, Sudan Archives and Walk the Moon, and alternative hip hop producer Hi-Tek calls the Metro Cincinnati region home. Andy Biersack, the lead vocalist for the rock band Black Veil Brides, was born in Cincinnati.

The Cincinnati May Festival Chorus is an amateur choir that has been in existence since 1880. The city is home to the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Cincinnati Opera, Cincinnati Boychoir, and Cincinnati Ballet. Metro Cincinnati is also home to several regional orchestras and youth orchestras, including the Starling Chamber Orchestra and the Cincinnati Symphony Youth Orchestra. Music Director James Conlon and Chorus Director Robert Porco lead the Chorus through an extensive repertoire of classical music. The May Festival Chorus is the mainstay of the oldest continuous choral festival in the Western Hemisphere. Cincinnati Music Hall was built to house the May Festival.

Cincinnati is the subject of a Connie Smith song written by Bill Anderson, called Cincinnati, Ohio. Cincinnati is the main scenario for the international music production of Italian artist and songwriter Veronica Vitale called "Inside the Outsider". She embedded the sounds of the trains at Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Downtown Cincinnati, filmed her music single "Mi Sono innamorato di Te" at the American Sign Museum and recorded her heartbeat sound at Cincinnati Children's Hospital replacing it to the drums for her song "The Pulse of Light" during the broadcasting at Ryan Seacrest's studio. Furthermore, she released the music single "Nobody is Perfect" featuring legendary Cincinnati's bass player Bootsy Collins.[115]

Cincinnati was a major early music recording center and was home to King Records, which helped launch the career of James Brown, who often recorded there, as well as Jewel Records, which helped launch Lonnie Mack's career, and Fraternity Records. Cincinnati had a vibrant jazz scene from the 1920s to today. Louis Armstrong's first recordings were done in the Cincinnati area, at Gennett Records, as were Jelly Roll Morton's, Hoagy Carmichael's, and Bix Beiderbecke, who took up residency in Cincinnati for a time. Fats Waller was on staff at WLW in the 1930s.

Theater

[edit]

Professional theatre has operated in Cincinnati since at least as early as the 1800s.[citation needed] Among the professional companies based in the city are Ensemble Theatre Cincinnati, Cincinnati Shakespeare Company, the Know Theatre of Cincinnati, Stage First Cincinnati, Cincinnati Public Theatre, Cincinnati Opera, The Performance Gallery and Clear Stage Cincinnati. The city is also home to Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, which hosts regional premieres, and the Aronoff Center, which hosts touring Broadway shows each year via Broadway Across America. The city has community theatres, such as the Cincinnati Young People's Theatre, the Showboat Majestic (which is the last surviving showboat in the United States and possibly[original research?] the world), and the Mariemont Players.

Since 2011, Cincinnati Opera and the University of Cincinnati College-Conservatory of Music have partnered to sponsor the Opera Fusion: New Works project. The Opera Fusion: New Works project acts as a program for composers or librettists to workshop an opera in a 10-day residency. This program is headed by the Director of Artistic Operations at Cincinnati Opera, Marcus Küchle, and the Head of Opera at CCM, Robin Guarino.

In 2015, Cincinnati held the USITT 2015 Conference and Stage Expo at the Duke Energy Convention Center, bringing 5,000+ students, university educators, theatrical designers and performers, and other personnel to the city.[116] The USITT Conference is considered the main conference for Theatre, Opera, and Dance in the United States.[citation needed]

Film and literature

[edit]A Rage in Harlem was filmed entirely in the Cincinnati neighborhood of Over the Rhine because of its similarity to 1950s Harlem. Movies that were filmed in part in Cincinnati include The Best Years of Our Lives (aerial footage early in the film), Ides of March, Fresh Horses, The Asphalt Jungle (the opening is shot from the Public Landing and takes place in Cincinnati although only Boone County, Kentucky, is mentioned), Rain Man, Miles Ahead, Airborne, Grimm Reality, Little Man Tate, City of Hope, An Innocent Man, Tango & Cash, A Mom for Christmas, Lost in Yonkers, Summer Catch, Artworks, Dreamer, Elizabethtown, Jimmy and Judy, Eight Men Out, Milk Money, Traffic, The Pride of Jesse Hallam, The Great Buck Howard, In Too Deep, Seven Below, Carol, Public Eye, The Last Late Night,[117] and The Mighty.[citation needed] In addition, Wild Hogs is set, though not filmed, in Cincinnati.[118]

The Cincinnati skyline was prominently featured in the opening and closing sequences of the CBS/ABC daytime drama The Edge of Night from its start in 1956 until 1980, when it was replaced by the Los Angeles skyline; the cityscape was the stand-in for the show's setting, Monticello. Procter & Gamble, the show's producer, is based in Cincinnati. The sitcom WKRP in Cincinnati and its sequel/spin-off The New WKRP in Cincinnati featured the city's skyline and other exterior shots in its credits, although was not filmed in Cincinnati. The city's skyline has also appeared in an April Fool's episode of The Drew Carey Show, which was set in Carey's hometown of Cleveland. 3 Doors Down's music video "It's Not My Time" was filmed in Cincinnati, and features the skyline and Fountain Square. Also, Harry's Law, the NBC legal dramedy created by David E. Kelley and starring Kathy Bates, was set in Cincinnati.[119]

The Hollows series of books by Kim Harrison is an urban fantasy that takes place in Cincinnati. American Girl's Kit Kittredge sub-series also took place in the city, although the film based on it was shot in Toronto.

Cincinnati also has its own chapter (or "Tent") of The Sons of the Desert (The Laurel and Hardy Appreciation Society), which meets several times per year.[120]

Cuisine

[edit]

Along with American cuisine, Cincinnati is host to numerous flavors infused from around the culinary world. Frisch's Big Boy, Graeter's ice cream, Kroger, LaRosa's Pizzeria, Montgomery Inn, Skyline Chili, Gold Star Chili, Aglamesis Bro's and United Dairy Farmers are Cincinnati eateries that sell their brand commodities in grocery markets and gas stations. Glier's goetta is produced in the Cincinnati area and is a popular local food. The Maisonette in Cincinnati was Mobil Travel Guide's longest-running five-star restaurant in the United States, holding that distinction for 41 consecutive years until it closed in 2005. Its former head chef, Jean-Robert de Cavel, has opened four new restaurants in the area since 2001.

One of the United States's oldest[122] and most celebrated[123] bars, Arnold's Bar and Grill in downtown Cincinnati has won awards from Esquire magazine's "Best Bars in America",[124] Thrillist's "Most Iconic Bar in Ohio",[125] The Daily Meal's "150 Best bars in America"[126] and Seriouseats.com's "The Cincinnati 10".[127] "If Arnold's were in New York, San Francisco, Chicago, or Boston—somewhere, in short, that people actually visit—it would be world-famous," wrote David Wondrich.[128]

The Filet-O-Fish was created in 1962 by Lou Groen, the owner of the first McDonald's franchise in the Cincinnati area, to cater to Catholic patrons who abstained from meat on Fridays.[129]

Traditional local delicacies include opera creams[130] and nectar soda,[131] both served at Graeter's and Aglamesis Bro's ice cream parlors. Grippo's and Pringles potato chips also have their origins in the area, the latter produced by local company Procter & Gamble. Other foodstuffs of local origin include Frank's RedHot sauce[132] and Slush Puppies.

Cincinnati chili

[edit]

Cincinnati chili, a spiced sauce served over noodles, usually topped with cheese and often with diced onions or beans, is the area's "best-known regional food".[133][134] A variety of recipes are served by respective parlors, including Skyline Chili, Gold Star Chili, and Dixie Chili and Deli, plus independent chili parlors including Camp Washington Chili, Empress Chili[135] and Moonlight Chili.[136] It was first developed by Macedonian immigrant restaurateurs in the 1920s. Cincinnati has been called the "Chili Capital of America" and "of the World" because it has more chili restaurants per capita than any other city in the United States or in the world.[137]

Goetta

[edit]Goetta is a meat-and-grain sausage or mush[138] of German inspiration. It is primarily composed of ground meat (pork, or pork and beef), pin-head oats and spices.[139]

Mock turtle soup

[edit]Similarly to goetta's origins, mock turtle soup was a dish popularized by the influx of German immigrants in the late 19th century. Originally made with offal, today Cincinnati-style mock turtle soup is characterized by ground beef, hard-boiled eggs, and ketchup. The only remaining commercial canner of the soup, Worthmore, has produced it in Cincinnati since 1918.[140][141]

Dialect

[edit]The citizens of Cincinnati speak in a General American dialect. Unlike the rest of the Midwest, Southwest Ohio shares some aspects of its vowel system with northern New Jersey English.[142][143] Most of the distinctive local features among speakers float as Midland American.[144] There is also some influence from the Southern American dialect found in Kentucky.[145] A touch of northern German is audible in the local vernacular: some residents use the word please when asking a speaker to repeat a statement. This usage is taken from the German practice, when bitte (a shortening of the formal "Wie bitte?" or "How please?" rendered word-for-word from German into English), was used as shorthand for asking someone to repeat.[146][147]

Sports

[edit]Cincinnati has three major league teams, three minor league teams, five college institutions with sports teams, and seven major sports venues. Cincinnati's three major league teams are Major League Baseball's Reds, who were named for America's first professional baseball team, the Cincinnati Red Stockings;[148][149][150] the Bengals of the National Football League; and FC Cincinnati, which became a Major League Soccer franchise in 2019. WalletHub has ranked Cincinnati as the No. 12 best sports city.

On Major League Baseball Opening Day, Cincinnati has the distinction of holding the "traditional opener" in baseball each year, due to its baseball history. Children have been known to skip school on Opening Day, and it is commonly thought of as a holiday.[151] The Cincinnati Reds have won five World Series titles, in 1919, 1940, 1975, 1976, and 1990. The Reds had one of the most successful baseball clubs of all time in the mid-1970s, known as The Big Red Machine.

The Bengals have made three Super Bowl appearances since the franchise was founded, in 1982, 1989, and 2022, but have yet to win a championship. The Bengals enjoy strong rivalries with the Cleveland Browns and Pittsburgh Steelers, both of whom are also members of the AFC North division. Whenever the Bengals and Carolina Panthers play against each other in an inter-conference matchup that occurs every four years, their games are dubbed the "Queen City Bowl", as Charlotte, North Carolina, the home city of the Panthers, is also known as the Queen City.[152]

FC Cincinnati is a soccer team that plays in Major League Soccer. FC Cincinnati made its home debut in the USL on April 9, 2016, before a crowd of more than 14,000 fans.[153] On their next home game against Louisville City FC, FC Cincinnati broke the all-time USL attendance record with a crowd of 20,497; on May 14, 2016, it broke its own record, bringing in an audience of 23,375 on its 1–0 victory against the Pittsburgh Riverhounds.[154] After breaking the USL attendance record on several additional occasions, the club moved to Major League Soccer (MLS) for the 2019 season.[155] FC Cincinnati was awarded an MLS bid on May 29, 2018, and moved to TQL Stadium in the West End neighborhood just northwest of downtown in 2021.[156]

Cincinnati is also home to two men's college basketball teams: the Cincinnati Bearcats and Xavier Musketeers. These two teams face off as one of college basketball's rivalries known as the Crosstown Shootout. In 2011, the rivalry game erupted in an on-court brawl at the end of the game that saw multiple suspensions follow. The Musketeers have made 10 of the last 11 NCAA tournaments while the Bearcats have won two Division I National Championships.[157] Previously, the Cincinnati Royals competed in the National Basketball Association from 1957 to 1972; they are now known as the Sacramento Kings.

The Flying Pig Marathon is a yearly event attracting many runners and acts as a qualifier to the Boston Marathon.

The Cincinnati Open, a historic international men's and women's tennis tournament that is part of the ATP Tour Masters 1000 Series and the WTA 1000 Series, was established in the city in 1899 and has been held at the Lindner Family Tennis Center in suburban Mason since 1979.

The Cincinnati Cyclones are a minor league AA-level professional hockey team playing in the ECHL. Founded in 1990, the team plays at the Heritage Bank Center. They won the 2010 Kelly Cup Finals, their 2nd championship in three seasons.

The Cincinnati Sizzle is a women's minor professional tackle football team that plays in the Women's Football Alliance. The team was established in 2003, by former Cincinnati Bengals running back Ickey Woods. In 2016 the team claimed their first National Championship Title in the United States Women's Football League.

The Kroger Queen City Championship debuted on the LPGA Tour in 2022 at Kenwood Country Club. It was the first time since 1963 that women's professional golf returned to Cincinnati.

The table below shows sports teams in the Cincinnati area that average more than 5,000 fans per game:

| Club | Sport | Founded | League | Venue | Avg attend | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cincinnati Reds | Baseball | 1882 | Major League Baseball | Great American Ball Park | 25,164 | [158] |

| Cincinnati Bearcats | Football | 1885 | NCAA Division I | Nippert Stadium | 33,871 | [159] |

| Cincinnati Bearcats | Basketball | 1901 | NCAA Division I | Fifth Third Arena | 9,415 | [160] |

| Xavier Musketeers | Basketball | 1920 | NCAA Division I | Cintas Center | 10,281 | [160] |

| Cincinnati Bengals | Football | 1968 | National Football League | Paycor Stadium | 66,247 | [161] |

| Cincinnati Cyclones | Ice hockey | 1990 | ECHL | Heritage Bank Center | 5,051 | [162] |

| FC Cincinnati | Soccer | 2015 | Major League Soccer | TQL Stadium | 21,199 | [163] |

Parks and recreation

[edit]

The Cincinnati Park Board maintains and operates all city parks in Cincinnati. Established in 1911 with the purchase of 168 acres (0.68 km2), today the board services more than 5,000 acres (20 km2) of city park space. Notable historic public parks and landscapes include the 19th-century Spring Grove Cemetery and Arboretum, Eden Park, and Mount Storm Park, all designed by Prussian émigré landscape architect Adolph Strauch.[164] The city also has several public golf courses, including the historic Avon Fields Golf Course.

Downtown Cincinnati towers about Fountain Square, the public square and event locale. Fountain Square was renovated in 2006.[165] Cincinnati rests along 22 miles (35 km) of riverfront about northern banks of the Ohio, stretching from California to Sayler Park, giving the Ohio a prominent place in the life of the city.[166]

The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden in Avondale is the second-oldest zoo in the United States.[167] It was appointed as a National Historic Landmark in 1987. The zoo houses over 500 species, 1,800 animals and 3,000 plant species. In addition, the zoo also has conducted several breeding programs in its history. The zoo is frequently cited among the best in the country.[168][169]

Government and politics

[edit]

The city proper operates with a nine-member city council, whose members are elected at-large. Prior to 1924, city council members were elected through a system of wards. The ward system was subject to corruption due to partisan rule. From the 1880s to the 1920s, the Republican Party dominated city politics, with the political machine of George B. "Boss" Cox exerting control.

A reform movement arose in 1923 which ended machine rule. It was led by another Republican, Murray Seasongood. He founded the Charter Committee, which used ballot initiatives in 1924 to replace the ward system with the current at-large system. They gained approval by voters for a council–manager government form of government, in which a smaller council hires a professional manager to operate the daily affairs of the city. From 1924 to 1957, the council was elected by proportional representation and single transferable voting. Starting with Ashtabula in 1915, several major cities in Ohio adopted this electoral system, which had the practical effect of reducing ward boss and political party power. For that reason, such groups opposed it.

In an effort to overturn the charter that provided for proportional representation, opponents in 1957 fanned fears of black political power, at a time of increasing civil rights activism.[170] The PR/STV system had enabled minorities to enter local politics and gain seats on the city council more than they had before, in proportion to their share of the population. This made the government more representative of the residents of the city.[171] Overturning that charter, in 1957, all candidates had to run in a single race for the nine city council positions. The top nine vote-getters were elected (the "9-X system"), which favored candidates who could appeal to the entire geographic area of the city and reach its residents with campaign materials. The mayor was elected by the council. In 1977, 33-year-old Jerry Springer, later a notable television talk show host, was chosen to serve one year as mayor.

To have their votes count more, starting in 1987, the top vote-getter in the city council election was automatically selected as mayor. Starting in 1999, the mayor was elected separately in a general at-large election for the first time. The city manager's role in government was reduced.[citation needed] These reforms were referred to as the "strong mayor" reforms,[by whom?] to make the publicate accountable to voters. Cincinnati politics include the participation of the Charter Party, the political party with the third-longest history of winning in local elections.[citation needed] On October 5, 2011, the Council became the first local government in the United States to adopt a resolution recognizing freedom from domestic violence as a fundamental human right.[172] On January 30, 2017, Cincinnati's mayor declared the city a sanctuary city.[173]

Cincinnati is home to the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, based in the Potter Stewart United States Courthouse. It has appellate jurisdiction over Kentucky, Michigan, Ohio, and Tennessee.

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Others |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 77.3% 106,620 | 21.2% 29,222 | 1.5% 2,126 |

| 2016 | 74.6% 100,876 | 21.3% 28,820 | 4.1% 5,590 |

Police and fire services

[edit]

The city of Cincinnati's emergency services for fire, rescue, EMS, hazardous materials and explosive ordnance disposal is handled by the Cincinnati Fire Department. On April 1, 1853, the Cincinnati Fire Department became the first paid professional fire department in United States.[175] The Cincinnati Fire Department operates out of 26 fire stations, located throughout the city in 4 districts, each commanded by a district chief.[176][177][178]

The Cincinnati Fire Department is organized into 4 bureaus: Operations,[177] Personnel and Training,[179] Administrative Services,[180] and Fire Prevention.[181] Each bureau is commanded by an assistant chief, who in turn reports to the chief of department.

The Cincinnati Police Department has more than 1,000 sworn officers. Before the riots of 2001, Cincinnati's overall crime rate had been dropping steadily and by 1995 had reached its lowest point since 1992 but with more murders and rapes.[182] After the riot, violent crime increased, but crime has been on the decline since.[183] The Cincinnati Police Department was featured on TLC's Police Women of Cincinnati and on A&E's reality show The First 48. Cincinnati had 71 homicides in 2023, down from 78 in 2022.[184]

Race relations

[edit]

Due to its location on the Ohio River, Cincinnati was a border town in a free state, across from Kentucky, which was a slave state. Residents of Cincinnati played a major role in abolitionism. Many fugitive slaves used the Ohio River at Cincinnati to escape to the North. Cincinnati had numerous stations on the Underground Railroad, but there were also runaway slave catchers active in the city, who put escaping slaves at risk of recapture.

Given its southern Ohio location, Cincinnati had also attracted settlers from the Upper South, who traveled along the Ohio River into the territory. Tensions between abolitionists and slavery supporters broke out in repeated violence, with whites attacking black people in 1829. Anti-abolitionists attacked black people in the city in a wave of destruction that resulted in 1,200 black people leaving the city and the country; they resettled in Canada.[185] The riot and its refugees were topics of discussion throughout the country, and black people organized the first Negro Convention in 1830 in Philadelphia to discuss these events.

White riots against black people took place again in Cincinnati in 1836 and 1842.[185] In 1836 a mob of 700 pro-slavery men attacked black neighborhoods, as well as a press run by James M. Birney, publisher of the anti-slavery weekly The Philanthropist.[186] Tensions increased after congressional passage in 1850 of the Fugitive Slave Act, which required cooperation by citizens in free states and increased penalties for failing to try to recapture escaped slaves.

Levi Coffin made the Cincinnati area the center of his anti-slavery efforts in 1847.[187] Harriet Beecher Stowe lived in Cincinnati for a time, met escaped slaves and used their stories as a basis for her novel Uncle Tom's Cabin (1852). The National Underground Railroad Freedom Center, which opened in 2004 on the Cincinnati riverfront in the middle of "The Banks" area between Great American Ballpark and Paul Brown Stadium, commemorates the volunteers who aided refugee slaves and their drive for freedom, as well as others who have been leaders for social justice.

Located in a free state and attracting many European immigrants, Cincinnati has historically had a predominantly white population.[81] By 1940, the Census Bureau reported the city's population as 87.8 percent white and 12.2 percent black.[81]

In the second half of the 20th century, Cincinnati, along with other rust belt cities, underwent a vast demographic transformation. By the early 21st century, the city's population was 40% black. Predominantly white, working-class families who constituted the urban core during the European immigration boom in the 19th and early 20th centuries, moved to newly constructed suburbs before and after World War II. Black people, fleeing the oppression of the Jim Crow South in hopes of better socioeconomic opportunity, had moved to these older city neighborhoods in their Great Migration to the industrial North. The downturn in industry in the late 20th century caused a loss of many jobs, leaving many people in poverty and homeless. In 1968 passage of national civil rights legislation had raised hopes for positive change, but the assassination of national leader Martin Luther King Jr. resulted in riots in many black neighborhoods in Cincinnati; unrest occurred in black communities in nearly every major U.S. city after King's murder.

More than three decades later, in April 2001, racially charged riots occurred after police fatally shot a young unarmed black man, Timothy Thomas, during a foot pursuit to arrest him, mostly for outstanding traffic warrants.[188] After the 2001 riots, the ACLU, Cincinnati Black United Front, the city and its police union agreed upon a community-oriented policing strategy. The agreement has been used as a model across the country for building relationships between police and local communities.[189]

On July 19, 2015, Samuel DuBose, an unarmed black motorist, was fatally shot by white University of Cincinnati Police Officer Ray Tensing after a routine traffic stop for a missing front license plate. The resulting legal proceedings in late 2016[190] have been a recurring focus of national news media.[191] Several protests involving the Black Lives Matter movement have been carried out.[192][193] Tensing was indicted on charges of murder and voluntary manslaughter, but a November 2016 trial ended in mistrial[194] after the jury became deadlocked. A retrial began in May 2017, which also ended in mistrial after deadlock. The prosecution then announced they did not plan to try Tensing a third time.[195] The University of Cincinnati has settled with the DuBose family for $4.8 million[196] and free tuition for each of the 12 children.

Education

[edit]Primary and secondary education

[edit]

Cincinnati Public Schools (CPS) include sixteen high schools all with citywide acceptance. CPS, the third-largest school cluster by student population in Ohio, was the largest to have an overall 'effective' rating from the State.[197][failed verification] The district currently includes public Montessori schools, including the first public Montessori high school established in the United States, Clark Montessori.[198] Cincinnati Public Schools' top-rated school is Walnut Hills High School, ranked 34th on the national list of best public schools by Newsweek. Walnut Hills offers 28 Advanced Placement courses. Cincinnati is also home to the first Kindergarten – 12th grade Arts School in the country, the School for Creative and Performing Arts.

The Jewish community has several schools, including the all-girl RITSS (Regional Institute for Torah and Secular Studies) high school,[199] and the all-boy Yeshivas Lubavitch High School.[200]

The Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati operates sixteen high schools in Cincinnati, ten of which are single-sex. There are six all-female high schools[201] and four all-male high schools in the city, with additional schools in the metro area.[202]

Higher education

[edit]

The Greater Cincinnati Collegiate Connection is a consortium consisting of all of the accredited colleges and universities in the Cincinnati area.

The University of Cincinnati is a public research university founded in 1819. It is the oldest institution of higher education in Cincinnati and has an annual enrollment of over 50,000 students, making it the second largest university in Ohio.[203] It is part of the University System of Ohio. The university's primary uptown campus and medical campus are located in the Heights and Corryville neighborhoods. The university is renowned in architecture and engineering, liberal arts, music, nursing, and social science. Notable divisions include the University of Cincinnati Medical Center and the College-Conservatory of Music.

Xavier University, a Roman Catholic college along with Mount St. Joseph University, was at one time affiliated with the Athenaeum of Ohio, the seminary of the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Cincinnati. Xavier is primarily an undergraduate, liberal arts institution based in the Jesuit tradition. Antonelli College, a career training school, is based in Cincinnati with several satellite campuses in Ohio and Mississippi. Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion (HUC-JIR), founded by Isaac Mayer Wise, is a seminary for training of Reform rabbis and others religious.

Cincinnati State Technical and Community College is a small technical and community college that includes the Midwest Culinary School. The Art Academy of Cincinnati, nicknamed AAC was founded as the 'McMicken School of Design in 1869. Also located in Cincinnati were Cincinnati Christian University and Chatfield College before they permanently closed in 2019 and 2023, respectively. Five hundred years since the Reformation Cincinnati provided a global distinguished lecture marking the layout of books and research for stirred city goers[204] and the Cincinnati Art Museum staff built Albrecht Durer: The Age of Reformation and Renaissance,[205] with more crafting by the university design, art, and architecture program given for the city.[206]

Libraries

[edit]The city has an extensive library system, both the city's public libraries and university facilities. The Cincinnati and Hamilton County Public Library system was the second largest in the nation by number of holdings in 2016.[207]

Healthcare

[edit]Media

[edit]

Newspapers

[edit]Cincinnati's daily newspaper is The Cincinnati Enquirer, which was established in 1841. The city is home to several alternative, weekly, and monthly publications, among which are free weekly print magazine publications including CityBeat[208] and La Jornada Latina. The city's weekly African American newspaper, The Cincinnati Herald, was founded by Gerald Porter in 1955 and purchased by Sesh Communications in 1996.

Television

[edit]

According to Nielsen Media Research, Cincinnati is the 36th largest television market in the United States as of the 2021 television season[update].[209] Twelve television stations broadcast from Cincinnati. Major commercial stations in the area include WLWT 5 (NBC), WCPO-TV 9 (ABC), WKRC-TV 12 (CBS, with CW on DT2), WXIX-TV 19 (Fox), WSTR-TV 64 (MyNetworkTV), and WBQC-LD 25 (Telemundo), which is a sister station to WXIX-TV through owner Gray Television's purchase of the station. WCET channel 48, now known as CET, is the United States' oldest licensed public television station (License #1, issued in 1951).[210] It is now co-owned with WPTO 14, a satellite of WPTD in nearby Dayton.

Radio

[edit]As of September 2022[update], Cincinnati is the 33rd largest radio market in the United States, with an estimated 1.8 million listeners aged 12 and above.[211] Major radio station operators include iHeartMedia and Cumulus Media. WLW and WCKY, both owned by iHeartMedia, are both clear-channel stations that broadcast at 50,000 watts, covering most of the eastern United States at night. Cincinnati Public Radio includes WVXU for news (an NPR member station) and WGUC for classical music.

Online

[edit]Soul Serum is a Cincinnati-based promotion and production company that provides the local music scene with live shows, music videos, podcasts, and more.[212]

Transportation

[edit]

Cincinnati has several standard modes of transportation including sidewalks, roads, public transit, bicycle paths and airports. The city's hills preclude the regular street grid common to many cities built up in the 19th century, and outside of the downtown basin, regular street grids are rare except for in patches of flat land where they are small and oriented according to topography.

Most trips are made by car, with transit and bicycles having a relatively low share of total trips; in a region of just over 2 million people, less than 80,000 trips were made with transit on an average day in 2012.[213] Like many other Midwestern cities, however, bicycle use grew rapidly in the 2000s and 2010s.[214] The city of Cincinnati has a higher than average percentage of households without a car. In 2015, 19.3 percent of Cincinnati households lacked a car and the figure increased slightly, to 21.2 percent, in 2016. The national average was 8.7 percent in 2016. Cincinnati averaged 1.3 cars per household in 2016, compared to a national average of 1.8.[215]

The development of a light rail system had long been a goal for Cincinnati, with several proposals emerging over many decades. The city grew rapidly during its streetcar era of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and is today served by the Connector. In 1917, citizens voted to spend $6 million (~$116 million in 2023) to build the Cincinnati Subway. The subway was planned to be a 16-mile (26 km) loop around the city hitting the suburbs of St. Bernard, Norwood, Oakley and Hyde Park before returning Downtown.[216] World War I delayed commencement of construction until 1920 and inflation raised the cost to over $13 million (~$150 million in 2023), causing the Oakley portion never to be built. Mayor Murray Seasongood, who took office later in the decade, argued it would cost too much money to finish the system, and construction stalled after the Wall Street Crash of 1929.

Public transportation

[edit]

The Connector streetcar line in Downtown and Over-the-Rhine opened for service on September 9, 2016, crossing directly above the unfinished subway on Central Parkway downtown.[52][53][217][218][219][220][221] Today the streetcar boasts over 3.5 miles of track and 16 hours of service per day on weekdays.[222] It had an annual ridership of over 846,000 in 2022.[223]

Cincinnati is served by the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority (SORTA), the Transit Authority of Northern Kentucky (TANK) and the Clermont Transportation Connection. SORTA and TANK primarily operate 40-foot (12 m) diesel buses, though some lines are served by longer articulated or hybrid-engine buses. SORTA buses operate under the "Metro" name and are referred to by locals as such.

A system of public staircases known as the Steps of Cincinnati guides pedestrians up and down the city's many hills. In addition to practical use linking hillside neighborhoods, the 400 stairways provide visitors with scenic views of the Cincinnati area.[224]

Cincinnati is served by Amtrak's Cardinal, an intercity passenger train which makes three weekly trips in each direction between Chicago and New York City through Cincinnati Union Terminal.

Roadways

[edit]

Bus traffic is heavy in Cincinnati. Several motor coach companies operate out of Cincinnati, making trips within the Midwest and beyond. The city has a beltway, Interstate 275 (which is the third-longest beltway overall in the United States at 85 miles or 137 kilometers) and a spur, Interstate 471, to Kentucky. It is also served by Interstate 71, Interstate 74, Interstate 75 and numerous U.S. highways: US 22, US 25, US 27, US 42, US 50, US 52, and US 127. The Riverfront Transit Center, built underneath 2nd Street, is about the size of eight football fields. It is only used for sporting events and school field trips. At its construction, it was designed for public transit buses, charter buses, school buses, city coach buses, light rail, and possibly commuter rail. When not in use for sporting events, it is closed off and rented to a private parking vendor.[225][226][227]

Air

[edit]The city is served by Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport (IATA: CVG) which is located in Hebron, Kentucky. The airport is a focus city for Allegiant Air and a global cargo hub for both Amazon Air and DHL Aviation.[228] The airport offers non-stop passenger service to over 50 destinations in North America and to European cities including Paris and London.[229] CVG is the 6th busiest airport in the United States by cargo traffic and is additionally the fastest-growing cargo airport in North America.

Other airports include Cincinnati Municipal Lunken Airport (IATA: LUK) which has daily service on commercial charter flights. The airport serves as a hub for Ultimate Air Shuttle and Flamingo Air.

Notable people

[edit]Sister cities

[edit]Cincinnati's sister cities are:[230][231]

See also

[edit]- City Plan for Cincinnati

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Cincinnati

- USS Cincinnati, 5 ships

- Vine Street, Cincinnati

Explanatory notes

[edit]- ^ Cincinnati's connection with Rome still exists today through its nickname of "The City of Seven Hills"[21] (a phrase commonly associated with Rome) and the town twinning program of Sister Cities International.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ Official records for Cincinnati kept at downtown from January 1871 to March 1915, at the Cincinnati Abbe Observatory just north of downtown from April 1915 to March 1947, and at KCVG near Hebron, Kentucky since April 1947. For more information, see Threadex and History of Weather Observations Cincinnati, Ohio 1789–1947.

References

[edit]- ^ a b Luten, Winifred (January 11, 1970). "How Losantiville Became The Athens of the West". The New York Times. p. 411. Archived from the original on June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 18, 2020 – via The New York Times Archive.

- ^ Greve 1904, p. 27: "The act to incorporate the town of Cincinnati was passed at the first session of the second General Assembly held at Chillicothe and approved by Governor St. Clair on January 1, 1802."

- ^ Greve 1904, pp. 507–508: "This act was passed February 5, 2851, and by virtue of a curative act passed three days later took effect on March 1, of the same year."

- ^ "ArcGIS REST Services Directory". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 19, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ^ a b U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Cincinnati

- ^ a b c "QuickFacts Cincinnati city, Ohio". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved May 16, 2024.

- ^ "Total Real Gross Domestic Product for Cincinnati, OH-KY-IN (MSA)". fred.stlouisfed.org. Archived from the original on October 21, 2019. Retrieved October 21, 2019.

- ^ "Zip Code Lookup". USPS. Archived from the original on February 11, 2012. Retrieved May 14, 2021.

- ^ "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on June 8, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "2020 Population and Housing State Data". United States Census Bureau, Population Division. August 12, 2021. Archived from the original on August 24, 2021. Retrieved August 14, 2021.

- ^ "When Cincinnati was 'the Paris of America'". Building Cincinnati. April 19, 2010. Archived from the original on April 19, 2012.

- Picturesque Cincinnati. Cincinnati, Ohio: John Shillito Company. 1883. p. 154. OCLC 3402849.

- Peterson, Lucas (July 13, 2016). "From Chili to the Underground Railroad, Cincinnati on a Budget". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 16, 2018.

- Morgan, Michael D. (2010). "Side-Door Sundays in the Paris of America". Over-the-Rhine: When Beer Was King. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 9781614231981. Archived from the original on March 27, 2024. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ a b "Cincinnati economy fastest-growing in the Midwest". Cincinnati.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved December 1, 2016.

- ^ Rieselman, Deborah. "Brief history of University of Cincinnati". UC Magazine. University of Cincinnati University Relations. Archived from the original on February 19, 2017. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- ^ "Top 10 Places For Young Professionals To Live – Forbes Advisor". www.forbes.com. Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 3, 2023.

- ^ Teetor, Henry Benton (May–October 1885). "Israel Ludlow and the naming of Cincinnati". Magazine of Western History. 2. Cleveland: 251–257.

The fair and reasonable presumption is that after consultation (certainly with Ludlow, the surveyor of the town, the proprietor of a two-thirds' interest in his own right, and as agent of Denman), St. Clair adopted the name suggested by Ludlow—a name which, as may seen from the following testimony, was not only mentioned for more than a year prior to the coming of St. Clair, but was selected and adopted by Denman, Patterson and Ludlow in the winter of 1788–9, and was inscribed upon the plat made by Ludlow to take the place of the one first made by Filson, which was destroyed in a personal altercation between Colonel Ludlow and Joel Williams.

- ^ Suess, Jeff (December 28, 2013). "Cincinnati's beginning: The origin of the settlement that became this city". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Archived from the original on March 17, 2019. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

On Jan. 2, 1790, Gen. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, came to inspect Fort Washington. He was pleased with the fort but disliked the name Losantiville. Two days later, he changed it to Cincinnati, after the Society of the Cincinnati, a military society for officers in the Continental Army during the Revolutionary War.

- ^ a b "How Cincinnati Became A City". Archived from the original on September 28, 2006. Retrieved December 11, 2006.

- ^ "46 Interesting Facts about Ancient Rome – Page 15 of 44". April 6, 2017. Archived from the original on June 23, 2018. Retrieved November 29, 2017.

- ^ Suess, Jeff (December 28, 2013). "Cincinnati's beginning: The origin of the settlement that became this city". Cincinnati.com. Archived from the original on March 17, 2019. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ "Cincinnati.com". Cincinnati.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2006. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- ^ Lossing, Benson (1868). The Pictorial Field-Book of the War of 1812. Harper & Brothers, Publishers. p. 476.

- ^ History of Cincinnati, Ohio. Cleveland, O., L.A. Williams & Co. 1881. Archived from the original on May 22, 2017. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- ^ Cincinnati: The Queen City Bicentennial Edition ISBN 0-911497-11-0, Cincinnati Historical Society, 1988, p. 15.

- ^ Suess, Jeff. "Our history: Who was Cincinnatus, inspiration for city's name?". The Enquirer. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ Greve 1904, pp. 507–508.

- ^ a b "Population of the 100 largest cities 1790–1990". The United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 14, 2007. Retrieved July 29, 2007.

- ^ a b c Condit, Carl W. (1977). The Railroad and the City: A Technological and Urbanistic History of Cincinnati. Ohio State University Press. ISBN 9780814202654.

- ^ a b Vexler, Robert. Cincinnati: A Chronological & Documentary History.

- ^ Suess, Jeff. "Why is Cincinnati called the Queen City?". The Enquirer. Archived from the original on January 25, 2021. Retrieved March 5, 2021.

- ^ "Lost City: Underground Railroad Sites - Cincinnati Magazine". Cincinnati Magazine. May 18, 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2018. Retrieved November 14, 2018.